Introduction

Few historical periods combined splendor and darkness as intensely as the Victorian era. It was the age of steam, scientific progress, and imperial expansion, but also a time of damp streets, extreme inequality, and crimes that permanently marked the collective imagination. Within this context, Victorian era murderers and mysteries emerged as a powerful reflection of a society divided between public morality and hidden impulses.

In this setting, the murderer ceased to be an invisible monster and became a cultural figure: a symbol of urban fear, moral decay, and the abyss separating appearances from reality. Victorian era murderers and mysteries were no longer isolated events but social phenomena that shaped how crime itself was understood.

Victorian mysteries not only filled newspapers and literature but also influenced the way we still perceive crime, guilt, and justice today.

London, capital of crime and mystery

London became the epicenter where Victorian era murderers and mysteries reached their highest symbolic expression, transforming the city into a permanent stage of moral and social tension.

A city of light and shadow

While Queen Victoria projected stability and order, London evolved into a moral labyrinth. The Industrial Revolution generated wealth—and misery. East End alleyways coexisted with aristocratic salons; fog concealed both factory smoke and the traces left by killers.

The city became a metaphor for the human soul: order and chaos sharing the same space, an ideal breeding ground for Victorian era murderers and mysteries.

Fear as entertainment

Newspapers quickly discovered the commercial value of panic. Reports of murders, disappearances, and anonymous confessions sold thousands of copies. Crime became spectacle, and the public grew accustomed to observing horror from the safety of printed pages.

This constant exposure normalized fear and cemented Victorian era murderers and mysteries as a regular presence in everyday life.

The birth of the modern murderer

The Victorian period marked the transition from individual crime to the concept of the murderer as a social and media phenomenon.

Jack the Ripper and the age of anonymity

Between 1888 and 1891, a series of murders in Whitechapel altered the history of criminality. For the first time, the killer had no clear identity. His anonymity made him immortal: evil became an abstract concept.

The letters signed “Jack the Ripper” inaugurated the media age of the serial killer, creating one of the most influential figures among Victorian era murderers and mysteries.

From reality to symbol

The Victorian murderer did not only destroy bodies but shattered certainties. He questioned faith in progress and exposed the cruelty hidden beneath civilization. Each crime revealed a social fracture: inequality, sexual repression, and urban alienation.

This was the dark side of the Victorian ideal, embodied by Victorian era murderers and mysteries as symbols of moral crisis.

The detective as a response to chaos

Opposing Victorian era murderers and mysteries, a new figure emerged: the rational investigator.

The need for order

If the 19th century created the media murderer, it also gave birth to the logical detective. Dupin, Holmes, and Poirot arose from the same collective anxiety—the desire for reason to overcome fear.

The detective symbolized trust in logic within a world destabilized by crime.

Science, deduction, and spectacle

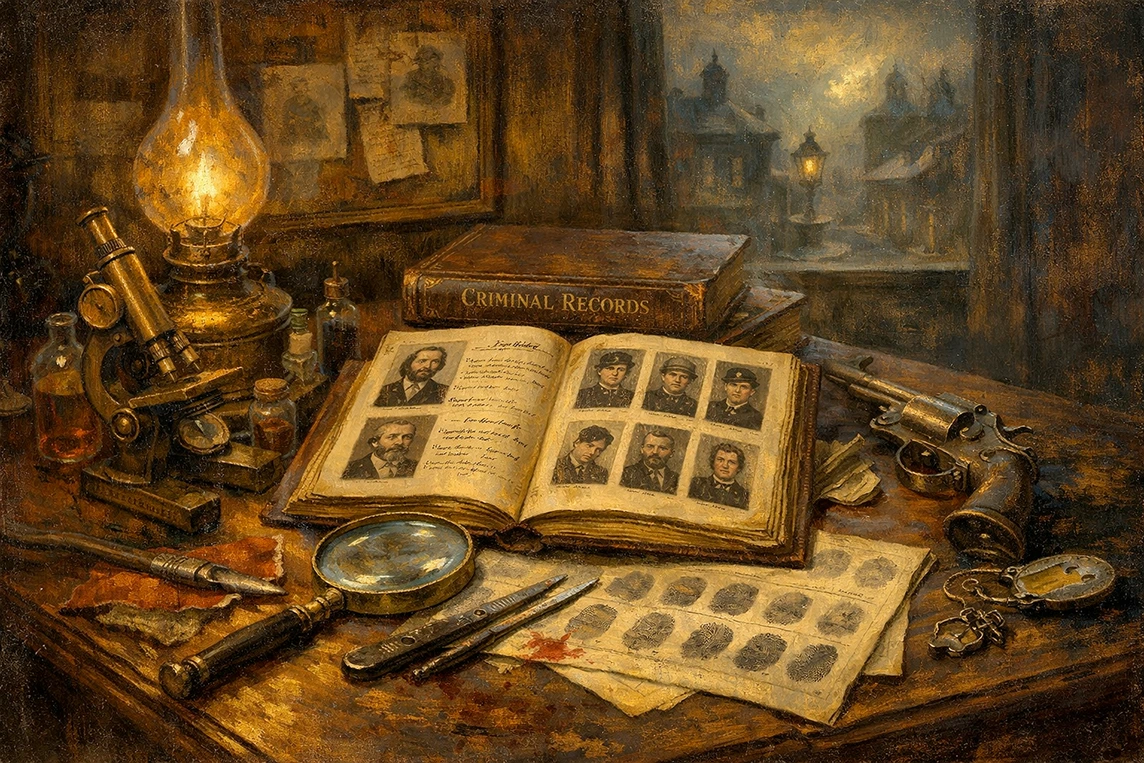

Criminology, forensic photography, and early police archives endowed investigation with scientific authority. Solving a crime became not only justice, but an intellectual performance.

Readers demanded more than punishment—they wanted method, reinforcing the narrative appeal of Victorian era murderers and mysteries.

Mystery as a social mirror

Victorian crime stories functioned as reflections of broader moral conflicts.

Crime and morality

Victorian murders were not merely police cases but moral parables. They exposed tension between virtue and desire, appearance and truth. Each mystery challenged the foundations of a society obsessed with respectability.

Women, the city, and fear

Female victims became symbols of vulnerability and repressed desire. Their portrayal in press and literature revealed both the misogyny of the era and its fascination with the destructive power of innocence.

In this sense, mystery was a dialogue about women’s roles and bodily control within a patriarchal society shaped by Victorian era murderers and mysteries.

Literature and the aesthetics of crime

Culture amplified the influence of Victorian crime narratives.

The influence of Poe, Dickens, and Stevenson

Edgar Allan Poe pioneered psychological analysis of murderers; Dickens explored the moral misery of industrial cities; Stevenson depicted duality between virtue and corruption in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Together, they transformed crime into moral allegory and reinforced the cultural weight of Victorian era murderers and mysteries.

The beauty of the macabre

Illustrators such as Gustave Doré and anonymous newspaper engravers created a lasting visual language of horror: cobblestone streets, solitary gas lamps, bodies covered by sheets. This imagery still defines the aesthetic of mystery today.

The legacy of Victorian mysteries

The cultural impact of this era remains powerful.

From penny dreadfuls to modern series

Modern thrillers still follow the Victorian blueprint: an inexplicable crime, a solitary investigator, and a moral revelation. Settings change, but emotional structure persists.

The enduring symbolic murderer

The appeal of the Victorian murderer lies in ambiguity. He does not kill purely for pleasure, but for motives society struggles to confront. He reminds us that civilization and barbarism are inseparable.

Conclusion

The Victorian era did not invent crime, but it transformed it into narrative. From its streets emerged the modern murderer, the rational detective, and the enduring obsession with understanding the human mind.

Victorian era murderers and mysteries continue to fascinate because they reveal that darkness does not belong to the past—it lingers in every attempt to understand ourselves. The fog may have lifted, but the echo of those footsteps still resonates in the shadows.