Introduction

The Victorian murderers that inspired Opus Mortis emerge from an era defined by extreme contrasts. The Victorian age was a time of industrial splendor and scientific progress, but also of misery, superstition, and moral repression. Beneath the glow of gas lamps and the promise of modernity, London society encountered a new and deeply unsettling form of fear: one that walked among them, hidden behind respectable appearances.

Victorian murderers—whether historically documented or transformed into legend—shaped the collective imagination of the nineteenth century. They became symbols of a society obsessed with morality, sin, guilt, and punishment. During the development of Opus Mortis, their influence was unavoidable. Each historical criminal was reimagined not as a literal portrait, but as a symbolic figure, a moral echo that transcends time.

“Victorian horror is not found in spilled blood, but in what it reveals about the human soul.”

— Opus Mortis narrative team

The Crime Context: London Beneath the Fog

To fully understand the Victorian murderers that inspired Opus Mortis, one must first understand their environment. By the late nineteenth century, London was a city of brutal inequalities. While the aristocracy filled theaters, opera houses, and private clubs, districts such as Whitechapel were consumed by poverty, overcrowding, and despair.

Crime became a silent form of protest—a distorted reflection of social inequality and moral corruption. Sensationalist newspapers magnified every murder, creating a fascinated and fearful public. For the first time, the murderer became a celebrity. This cultural phenomenon left a lasting mark on literature and art, and more than a century later, it directly influenced the symbolic and psychological narrative of Opus Mortis.

Jack the Ripper: The Myth of the Shadow

No figure represents the Victorian murderers that inspired Opus Mortis more powerfully than Jack the Ripper. His crimes in 1888 were never solved, and that absence of resolution created the most disturbing element of all: a moral void.

Beyond the gruesome details, Jack embodied the collapse of trust in social order. The killer was invisible, intelligent, and unpredictable. This sense of an unseen, omnipresent threat directly inspired the hidden killers of Opus Mortis, where evil is rarely visible but always felt.

“We wanted players to feel the same uncertainty as the citizens of Whitechapel—looking around and never knowing whom to trust.”

— Lead designer of Opus Mortis

Mary Pearcey: The Domestic Tragedy

Not all Victorian murderers that inspired Opus Mortis were driven by madness or cruelty alone. Some crimes emerged from passion, humiliation, and desperation. Mary Pearcey, executed in 1890 for the murder of her lover and his wife, became a symbol of Victorian fears surrounding female transgression.

Her story reveals the violence hidden within the domestic sphere. In Opus Mortis, this archetype appears in female characters shaped by guilt, desire, and social repression. The moral question raised by this figure remains timeless: how far can injustice push a wounded soul?

Thomas Neill Cream: The Doctor of Death

Among the Victorian murderers that inspired Opus Mortis, Thomas Neill Cream stands as a representation of rational evil. A physician and serial poisoner, he was one of the earliest criminals to use scientific knowledge as a tool for murder.

His crimes reflect a distinctly modern fear: progress without ethics, intellect divorced from morality. In Opus Mortis, this profile evolves into characters who seek redemption through knowledge but are ultimately consumed by it. Cream is not portrayed literally; instead, his legacy becomes the archetype of the corrupted scholar—one who seeks to understand everything and ends up destroying everything.

Amelia Dyer: Darkness Behind Charity

Amelia Dyer represents another crucial figure among the Victorian murderers that inspired Opus Mortis. Known as the “baby farmer,” she hid behind a façade of respectability and charity while trafficking and murdering abandoned infants.

Her story embodies Victorian moral hypocrisy: virtue as a mask for horror. This duality between appearance and sin is deeply embedded in Opus Mortis. Players quickly learn that good intentions cannot be trusted at face value. In this universe, evil often wears the disguise of compassion.

Crimes Without Names: The Collective Echo of Fear

Many Victorian murderers that inspired Opus Mortis were never remembered by name, yet their influence endured. Tabloids turned them into symbols, moralists into warnings, and artists into sources of inspiration.

This fusion of reality and myth forms the foundation of the game’s atmosphere: a city where every crime is a metaphor, and every murderer reflects a deeper truth about human nature.

“In our universe, no murderer exists without cause. Every one of them is the result of a society that chooses to look away.”

— Opus Mortis screenwriter

From History to Myth: The Legacy Within Opus Mortis

Rather than recreating real crimes, Opus Mortis reinterprets the symbolic legacy of the Victorian murderers that inspired Opus Mortis. Jack’s blade becomes an obsession with purity; Dyer’s false charity becomes a mechanic of moral deception; Cream’s science transforms into power that consumes its wielder.

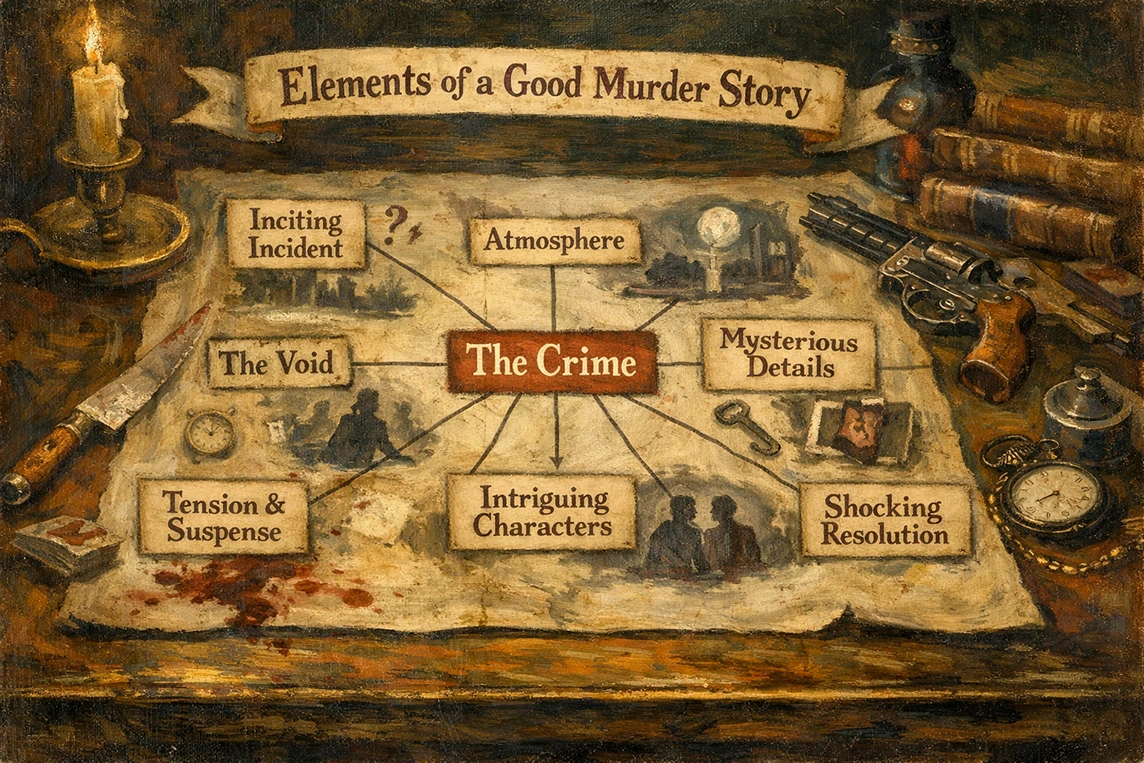

Each fictional murderer in the game carries a fragment of this cultural heritage, translated into the language of board game mechanics and psychological horror.

Conclusion: Crime as a Moral Reflection

The Victorian murderers that inspired Opus Mortis were more than historical criminals. They were symptoms of a society consumed by fear, repression, and desire. Within Opus Mortis, their echoes remain alive, reshaped into metaphors of the human soul.

Players are not asked to judge these figures, but to understand them. Because in understanding the murderer, we ultimately confront our own shadows.